Birmingham Gothic

The city's planners and politicians never were much interested in its history, architectural or otherwise. But a few neglected gems from the city's Victorian high point remain.

For a city built by the Victorians, there aren’t too many Gothic Revival buildings still standing in our once-mighty Second City. Like Rome without the Romans.

Birmingham likes to demolish. The Victorian City library, old New Street and Snow Hill stations (think St Pancras), plus many Victorian-era hotels, assembly halls, theatres and commercial terraces were all swept away in the Brutalist purge of the 1950s and 60s.

So many Victorian buildings, and much of the city was levelled as planners and politicians set out to totally remodel, with one eye on the freeways of LA, and another on the vast new covered shopping malls of US states such as Minnesota.

Fast forward to the early 1990s and the city was about to be completely uprooted and overturned once more. After years of economic decline, city bosses decided once and for all to throw in the towel on manufacturing and replace it with… Culture. A new economy was to be built around leisure and tourism and planners got busy chopping and changing, and generally upending whole swathes of the city once again. But that’s a story for the next post.

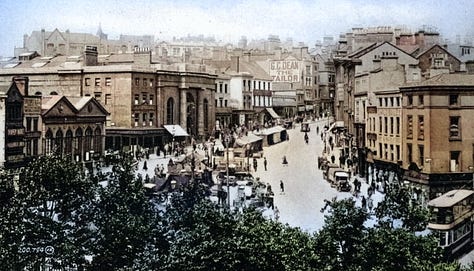

One corner of the city survived both city council masterplans, and remains largely unscathed, if a bit neglected and unloved. At the very end of Corporation Street – Joseph Chamberlain’s grand boulevard - sloping northwards to the very edge of the city centre, is what might be described today as Birmingham’s Gothic Quarter.

Sitting proudly and unscathed are two Victorian giants. On the left the Victoria Law Courts and opposite, the Central Methodist Hall. Birmingham’s Terracotta Twins.

The Law Courts were built in 1891 by London-based architects Aston Webb and Ingress Bell, who beat 126 others to win the commission. Webb designed the facade of Buckingham Palace, the main buildings of the Victoria and Albert Museum the University of Birmingham.

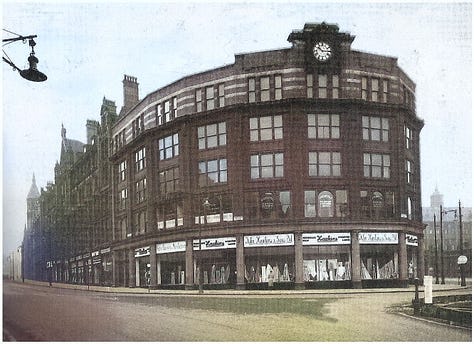

The Central Methodist Hall opposite, is three-storey complex, designed by Birmingham architects Ewen and Alfred Harper. It consisted of a main hall to seat 2,000 and over thirty other rooms including three school halls. At ground-level the building faces onto the street with a row of neatly presented shops and commercial units. Like the great building itself, many of the shops are now closed and boarded up.

Okay so it’s not quite Gothic, more neo-Romanesque, but really it’s more of a Victorian terracotta mash-up, with Greek Ionic columns, “turrets resembling Indian chattris”, elements of Baroque “Art Nouveau flourishes” as well as Gothic and Romanesque.

As critic Alexandra Wedgwood said in 1966, it is “clearly the local men’s answer to the Victoria Law Courts opposite, to which it does indeed form the perfect complement.”

To Birmingham Victorians it might well have been conceived of more as judicial, moral and educational quarter or campus. As well as the Terracotta Twins, Steelhouse Lane police station sits just behind the Law Courts and is even connected by a series of tunnels that give “direct access from cell-to-courtroom”.

Around the corner from the Methodist Hall is of course Aston University, which began life as the Birmingham Municipal Technical School in the 1890s. The original building looks very much like another Victorian Terracotta mix, though RIBA describes the style as Queen Ann.

So, it is perhaps a city neighbourhood defined by a body of ideas and values more than architectural style. Which is no surprise, given the reputation of the city under Mayor Joseph Chamberlain, businessman-turned-politician and pioneer of Victorian municipalism. Under Chamberlain, Birmingham built a reputation for being the most well-run city in the world. How fortunes change.

The Law Courts and the Methodist Hall maybe Grade I and Grade II Listed, but no one told the pigeons, nor the weeds and shrubbery protruding from towers, walls and windowsills. Many of the elegant shop units under the Methodist Hall are boarded up or sell little of interest. The Methodists left town many years ago, and until a few years ago the building was used as a nightclub. But now it sits empty and abandoned.

Neglect of the buildings is one thing. For now at least, it’s probably no bad thing that this old bit of the city has been forgotten. Heritage listing may offer protection from demolition. It’s entirely possible however that Birmingham’s forgotten Gothic Quarter will find itself in the crosshairs of the Decolonisers and the professionally-traumatised. The recent case of the Albert Memorial custodians - Royal Parks - branding it as offensive, because it “represents a ‘Victorian view of European supremacy” is a may be a worrying sign of things to come.

But the really striking thing, more than the neglected architecture, is the absence of city social and commercial life. It feels like a whole part of the city that has lost its spirit and its purpose.

It's a far cry from when I discovered this area as a teenager in the early 1980s. A century on from Chamberlain it was still a thriving, vital part of the city, driven perhaps by the many lawyers and legal firms who kept the many pubs and shops and bars open and thriving.

At the very end of Corporation St, as the terrace that formed out of the law courts swept around towards Steelhouse Lane police station sat Hawkins Wine Bar.

Hawkins, like the Rum Runner club on Broad St (ironically forced to close by the City Council to make way for it’s conference and entertainment quarter) , was a rare stylish hangout, where chicly-dressed young Brummies met, drank espresso, cocktails, listened to jazz-funk and soul, and dreamt of New York or Paris.

The mid-to-late 70s was a moment when the style, glamour of the 1930s and early 40s was very much back in fashion. People liked to dress up!

The Rag Market was a great place for stylish vintage wear, and there were plenty of small fashion outlets such as New Romantics ‘Kahn and Bell’ and nearby Oasis market (more like a labyrinthine bazar of independent fashion outlets, vintage clothes, and records), where Vivienne Westwood had an outlet, Boy George worked briefly and where I first discovered the Face magazine.

Hawkins’ pièce de résistance was a towering ornate Gothic backbar - bought by the owners from an old church - that was lit up by neon lights in the evening. It’s the kind of architectural feature we are not unused to seeing in swish bars today, but not in 1970s Birmingham.Top of Corporation St was also a gateway into a more artsy part of the city. Aston University may be known for engineering and economics, but its Gosta Green campus (more like a city park) was also home to the Triangle Cinema and Arts Centre and a couple of the city’s best pubs, the Sack of Potatoes and the Gosta Green.

The Triangle started life in the late 1960s as the Arts Lab, which specialised in experimental theatre, film and contemporary art. In the late 70s it was incorporated into Aston Uni, rebranded and rehoused in Gosta Green. By the time I discovered it, as a student in the mid 1980s, it was principally a cinema, showing European classics and new releases like Betty Blu and Almodovar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

And they continued to host art exhibitions, live bands and even Jamaican ‘sound clashes’. I saw Lewisham’s Saxon Sound, as well as Sugar Minot’s Youth Promotion when they were over from Jamaica. Both were hugely popular in dancehall reggae at the time and Gosta Green was absolutely rammed on both occasions. These were not the kind of gigs you would find at an arts centre back then. So that part of the city was really something unique, at least for a while.

During the 1990s, as politicians began to use culture as an instrument for reinvention and regeneration, but Birmingham already had a cultural life, largely driven by the passions and aspirations of the people themselves.

Under the council the arts became more regulated, safe and ultimately top-down. It was now an ‘industry’, organised by ‘arts professionals’ and ‘arts managers’ and arguably we, the public were reduced to passive consumers of ‘culture’.

Whatever the successes or failures of the city council’s policies over the last 30 years, this once thriving area has lost its mojo. Fortunately it’s still beautiful and has bags of potential.

It certainly doesn’t need another of the council’s dodgy masterplans, but it could do with some imaginative, independent-minded groups or individuals to make things happen again. There’s lots of empty space and much to inspire. If we could recapture some of the Victorian spirit, civic pride, independence and entrepreneurial zeal, that would indeed be a step in the right direction.

Forward, as the city’s motto goes.