Smethwick: Postwar history, family mystery

Reflections on the history and troubles of this once mighty industrial town where Charlie Chaplin was born in a gypsy caravan and Malcolm X came to find 'Nazi gas chambers'

Smethwick. Little old post-industrial town north of Birmingham. My brother Rob is currently in convalescence at a nursing home there and I go see him whenever I can, which is not often enough. Life gets in the way, as does the price of a train ticket. Whatever happened to cheap intercity travel? HS2 anyone?

I enjoy my brief time with my brother, and I like being back in my old stomping ground. I failed my A levels in Smethwick, I had some fun times at college and met some of my best friends in Smethwick, I lived there for a while in the mid 1980s, plus I have deep family and social connections – the kind of things that interest you more as you get older, especially since my uncle’s digging into our family history has turned up stories and mysteries that all seem to centre on Smethwick.

Then there’s my interest in history. Birmingham’s historical role in the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, which spilled over into Smethwick, with Boulton and Watt’s Soho Foundry, the world’s first purpose-built steam engine factory’. The twin canals of James Brindley and Thomas Telford, that cut through the town, linking Birmingham to many of the Black Country towns, and ultimately the River Severn at Stourport.

So here I am again. One stop from New Street and I jump off at ‘Smethwick Rolfe Street’. Rolfe Street – the street – is pretty baren and uninviting. If Smethwick had tumbleweed it would be rolling up and down Rolfe Street.

It pains me to say it looks so dead and uninteresting, because my grandfather Burt Smith, whom I never knew, and generations of his/my family lived and worked there. It had been a thriving commercial centre, long before my time. It had a Grand Theatre, where Smethwick Operatic Society used to perform! But that was demolished in 1932! I do remember Rolfe Street Baths. That lasted into the 1980s, until it was dismantled brick-by-brick and reassembled at the Black Country Museum.

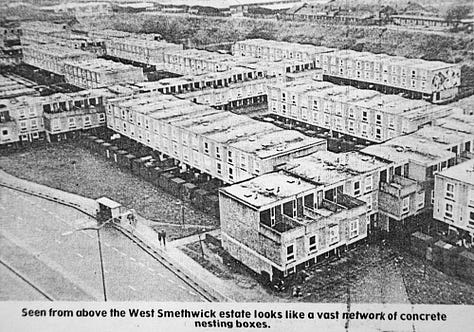

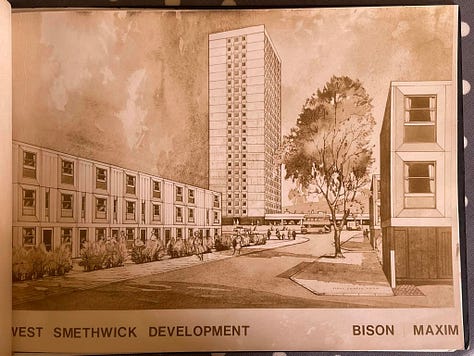

I exit the station and turn left. My brother’s place is over the High Street and up the hill, behind the picturesque Holy Trinity Church. Straight ahead, the train continues north, following the cut of the canals, past the restored Victorian pumping station – now a Lottery-funded canal museum that - sadly - rarely opens. The next station, half a mile along the canal is ‘Smethwick Galton Bridge’ nee Spon Lane, nee ‘Concrete Jungle’, the name given by locals to the 1960s council estate next to the station.

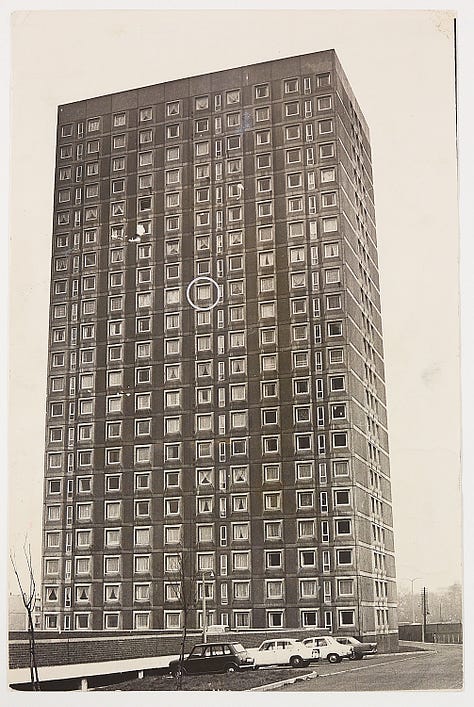

The ‘Jungle’ was collection of flat-roofed rectangular town houses, prefabricated from blocks of textured concrete and with a ground-level ‘carport’. To me they looked kind of Brutalist and Moorish, especially when they were painted creamy-white in the early 80s. Keeping guard over the Jungle were Malthouse Point and Sandfield Point, two not-very-pointy 22-storey towers made from the same prefabricated Lego blocks. My uncle John lived in one of them. Not sure which.

The Points were demolished in the 80s, but the town houses were reclad in red brick, topped off with -traditional - pitched roofs and given another chance. My sister Sharon was one of the new post-revamp residents, but it wasn’t long before the estate’s destiny caught up with it once more, and it became a place where you really didn’t want to be.

The station was also spruced up and in another nod to the past, renamed ‘Galton Bridge’, after the other of Thomas Telford’s local engineering marvels. Galton Bridge is/was ‘the longest canal bridge over the deepest cutting in the world’ – it’s a beautiful but now-redundant Victorian marvel.

So left then, and out of Rolfe Street Station towards the High Street – just a hop and a skip over the foreboding four-lane A457 that scythes by, on the edge of town, taking half of the old High Street (demolished early 80s) with it. It scythes on, through home town of Oldbury towards the M5.

Standing at the crossings, waiting for the lights to change, I face Guru Nanak, the ice-blue marbled, ever-expanding Gurdwara (ਗੁਰੂ ਨਾਨਕ ਗੁਰਦੁਆਰਾ ਸਮੈਦਿਕ), Britain’s oldest (est 1958) Sikh temple, and now, allegedly the largest outside India. It has evolved over the years, out of an old church, since gobbling up neighbouring buildings including the derelict Art Deco Prince’s Cinema, something that still saddens me.

It’s no Golden Temple of Amritsar but these days it’s quite imposing and impressive - way more grand than when I lived in the town 40 years ago. You might describe it as incongruous or out of place, but if you look down the High Street towards Oldbury (above, right), you can see that the Gurdawa’s grand gold and white ‘onion’ dome lines up nicely with some much older Orient-inspired Victorian domed buildings along the same terrace.

Look again and you’ll see at the very end of the street about half a mile away, sits another – new - golden Sikh dome, atop of a former music hall, where local legend has it that Charlie Chaplin once performed. If you watched Peaky Blinders you’ll probably know that all his life Chaplin’s. birth and humble Smethwick origins were a mystery which he kept secret all his life. So, by chance were my grandmother’s. And her secret is still hidden away, in one of those buildings next to the old music hall.

In the modest treelined square between the temple and the four-lane destroyer of towns stands the ‘Lions of the Great War’, a sculptural memorial to Indian servicemen who fought for Britain during both world wars.

Luke Perry’s traditional and imposing 10ft bronze soldier –Sikh turban, military trench coat and rifle over his shoulder - was unveiled, to much fanfare in 2018. Sharon was there with friends, amongst the crowds of local people, young and old, all backgrounds, proudly followed a military marching band along Smethwick High Street.

Less than a week later Smethwick made the national and international news. ‘Racist vandals deface Sikh soldier war memorial’ cried the Daily Mirror, and the BBC called it a ‘Race hate vandal attack’, Birmingham Mail reported it as a ‘racially aggravated attack’. No! Was my first reaction. No, as in ‘Not True, not racism’, as in I don’t believe it! as in ‘Don’t be ridiculous. I’m sure most other people in and from Smethwick thought the same.

Ironically it was the Times of India that took a more measured approach, pointing out that both the police and the British ‘presumed it was a racist attack’ but suggesting it was most likely the work of a young self-styled ‘anti-imperialist’ Sikh group, who objected to Indian soldiers fighting for their ‘colonialist oppressors’ in the Great Wars. And so it turned out to be.

No local racists and no apology from the police, no retraction from the press.

Of course, we’ve become used to British press, politicians, police, media personalities, and state institutions branding people racists with abandon, especially working class communities in Midland and Northern towns outside London. But accusations against Smethwick go back much much further. It has a rap sheet! In fact it has even been branded ‘the most racist town in Britain’. More than once.

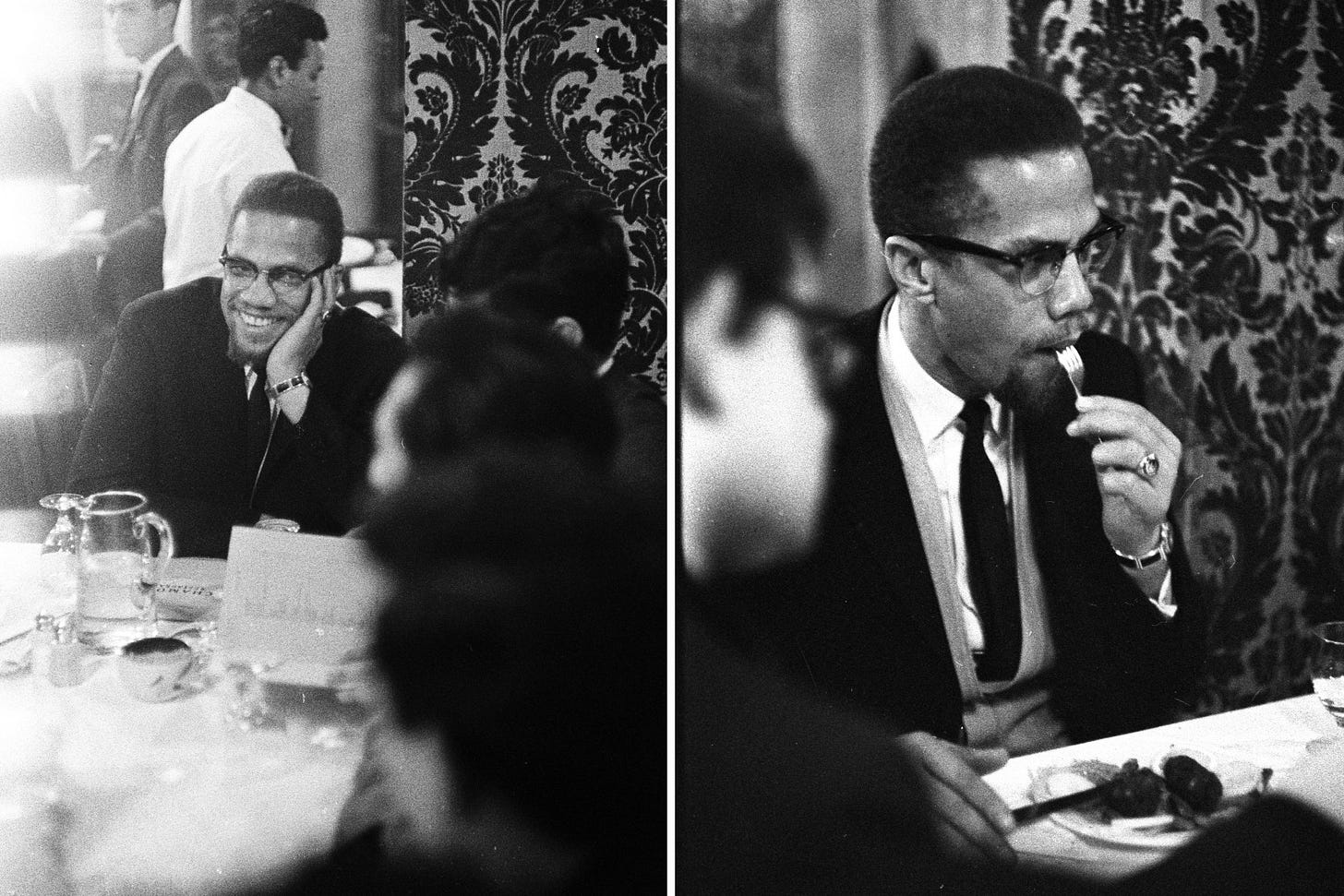

Sixty years ago, such was the reputation of the town that US Black Civil Rights campaigner Malcolm X no less, visited Smethwick - February 1965 - to see what was going on. He told the BBC he’d had heard that ‘coloured people in Smethwick’ were ‘being treated as the Jews were under Hitler’, and had wanted find out for himself.

During his brief visit, Malcolm X was filmed and photographed walking along Marshall Street, where he talked (privately) to black residents about their experiences, and visited the Blue Gates, the most well known pub on the High Street.

He was apparently refused service in the pub’s ‘lounge’ (remember them?) due to what has been reported as an ‘informal colour bar’. So he went instead to the bar and had a drink with the local Indians and West Indians. From what I remember, growing up, is that the Pub Lounge was often a very cliquey place, with various restrictions in place and frequented usually by ‘ladies’ sipping Babycham. But I’m sure racism had much to do with it. Casual racism was rife even when I was growing up in the 70s.

“I have heard they (‘coloured people’) are being treated as the Jews under Hitler. I would not wait for the fascist element in Smethwick to erect gas ovens.” Malcolm X

Brother Malcolm had been invited to Smethwick by the radical left group the Indian Workers Association, following the now infamous 1964 General Election - ‘Britain’s most racist election’, which was marred by a really nasty racist campaign in Smethwick that has rightly gone down as a low point in British social and political history.

Conservative candidate Peter Griffiths stood, and was elected as MP for Smethwick, apparently on the back of the slogan ‘If you want a n****r for a neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour’. It was not an official campaign slogan, but Griffiths, a local headmaster, claimed the phrase was “a manifestation of popular feeling”. I’ll come back to that in a later post.

It was an unexpected result and it went against the general mood of the country - Labour won the election and Harold Wilson was swept to power. Smethwick stood out as the nation’s bad boy.

On the 50th anniversary of Malcolm X’s visit, the Guardian claimed that 1960s Smethwick was ‘the most racist place in Britain’. Other papers and commentators followed a similar line. It will be interesting to see what they and the left-liberal media have to say come the 60th anniversary in February.

“I am always shocked that many local people don’t know about this important event in our recent history” said playwright Paul Megson, after receiving an Arts Council grant to write a play about Malcolm X’s 1965 visit to the town. “The politics and issues of the time have never been more relevant as we grapple with hate crime, Brexit, ‘fake news’.” he warned. Hmm.

Some critics suggest that the town’s racist roots go further back, pointing out that the Oswald Moseley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, was once a Smethwick MP. Of course Sir Oswald was actually a Labour MP when he represented Smethwick. He went on to form his Fascist party in the 1930s.

Had the people of Smethwick erased Malcolm X’s visit from their historical memory? I only found out about his visit by chance when stumbled across the now famous Marshall Street photo, while Googling something or other.

I was stunned. How could one of the most important and famous political figures of the twentieth century be in Smethwick, just eight days before he was assassinated and six weeks before - just up the road - I was born? How close we came to our paths crossing!

The answer is it just wasn’t publicised. It wasn’t considered ‘newsworthy’. And why would most people in England even know who he was? If anyone was operating a colour bar in Britain back then it was the BBC and the establishment.

The BBC had filmed and interviewed Malcolm X in Smethwick, but it was never broadcast and was instead confined to the archives for half a century. In 2014 the Daily Mirror called it one of the ‘defining moments of the 1960s’ but the visit of one of the most famous people in the world didn’t even make the local papers. The assassination of Malcolm X, nine days, later barely even made the front pages of UK national newspapers.

Lucky for posterity that The Sunday Times sent photographer Kelvin Brodie to capture images of the civil rights campaigner in Smethwick, but again, it didn’t publish the pictures or the story. Little wonder then that many people didn’t know about this ‘defining moment’ of a century-defining decade.

A year later BBC TV made, and this time broadcast, an investigative programme about racial discrimination in Smethwick. The documentary set out to show how the town’s burgeoning immigrant population faced routine discrimination in pubs, shops, places of worship, housing and of course the workplace.

A local Indian man agreed to wear a concealed BBC microphone and set off to to get a haircut. "We're closed now," he recorded the barber saying. "Will you clear off?” When his visitor challenged him, insisting there was no sign in the window, and that the salon was not closed, the hairdresser replies: "Well I am. To you.”

Well this is all starting to sound more 1960s Birmingham Alabama than Birmingham England. Was our town the most racist in Britain? In many ways quite the opposite. Without wishing to minimise the problems that postwar immigrant communities have faced over the years, I’ve always believed Smethwick has much to teach us about racial integration, if we take the time to actually look and not simply confuse historical events in Britain either with Fascism or the Black American experience.

But that’s for part two…