Way down in the hole!

Holes large and small were a surprisingly important part of the Black Country economy and mythology. Dudley and Oldbury had so many, it's a wonder these neighbouring towns didn't disappear altogether.

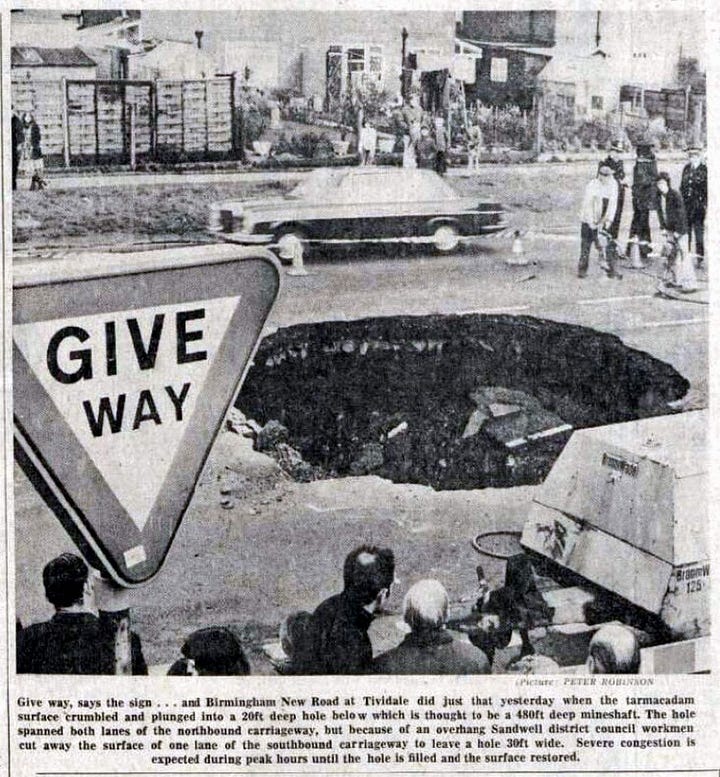

I’ve been looking for an excuse to talk about holes for as long as i can remember. Such opportunities don’t open up too often. My chance finally arrived when an old local (Midlands) news article popped up on my Facebook timeline this week. The year 1977 and a ‘giant’ hole appeared on the main Wolverhampton to Birmingham Road. I remember the incident, because the Wolvo - as it was colloquially known - crosses the estate where I grew up, though the 30ft wide hole appeared a couple of miles north of us, towards Dudley.

No one was hurt and the road was quickly repaired and reopened (imagine that today!). However, everyone in our neighbourhood knew that drivers had a lucky escape, as just a few years earlier another, much larger hole had opened up on a nearby football pitch, taking most of the midfield with it, never to be seen again! Fact!

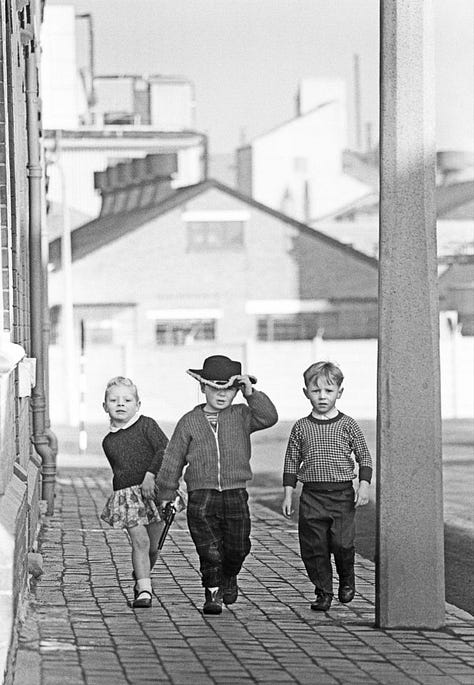

But was it? It was certainly part of local folklore, according to which, holes were opening all the time and swallowing people up, especially naughty children. Or so our parents used to say.

Given given the history of the area it was entirely possible something terrible happened. The Black Country only really existed because it sat on top of an enormous coal seam just below the surface. The seam came up to the surface in and around at least 12 of the Black Country’s towns. More than a century of digging and mining went largely unmapped - who knew where there were mineshafts, tunnels or how they had been sealed or filled in?

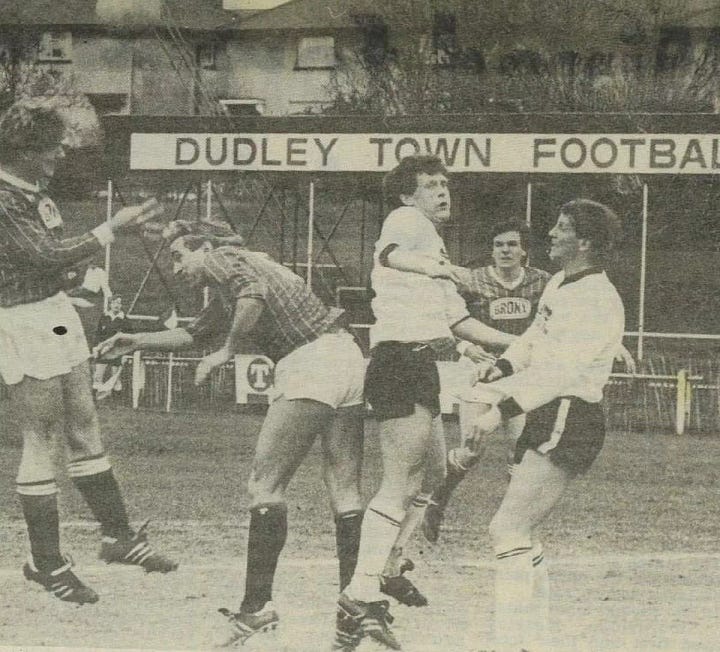

In fact, in 1985 a hole really did open up at Dudley Town Football ground, or rather an adjacent cricket pitch, and some of the players had a lucky escape. The club’s former Treasurer Brian Woodhall recalled to the local paper his friend’s close call:

"Then I heard the wicket had collapsed and John had been forced to run for his life fearing he’d be swallowed up by the disintegrating ground. Later it transpired that the ground had split only a few inches wide but the drop was well over 75 feet.”

In this case the problem was due to old limestone workings, and the sports ground was forced to shut permanently and the Dudley Town had to find a new home.

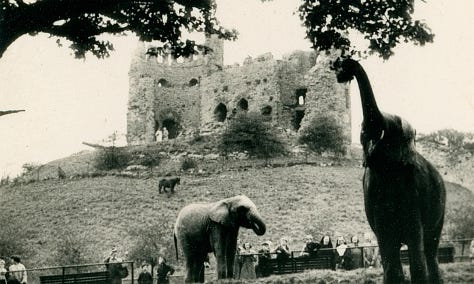

Still, when it came to holes and what was down them, it was sometimes difficult to separate myth from reality, especially when you were nine years-old. For instance, everyone knew Dudley had caves and caverns and that one of them led directly from the lion enclosure in Dudley zoo right to Brandhall Golf Course at the top of our estate. Fact!

Were these caves and tunnels natural? Did they predate the Industrial Revolution? Were they escape routes for Royalists fighters and supporters aligned with the Earl of Dudley during the English Civil War? Who could say?

All we knew was we were always at risk of lion attacks whenever we played over the golf course, which itself existed thanks to holes - all 18 of them. Recreational holes, you might say. For us kinds and locals though, it was essentially a huge park, with gently rolling hills, a brook and coppices to play in.

As it happened, a network of tunnels and caverns had in fact been dug out of the limestone under Dudley in the C19th. According to the BBC

“The limestone caves in Dudley were carved out by the mining industry, hauling away 1,000 tonnes of limestone a week which was used to remove impurities from iron ore... Today, the caves remain and are used for many purposes, with everything from boat trips to weddings, ghost tours and concerts being held there.”

Lucky for us, these surprise holes tended to open up closer to Dudley, a place full of strange things and strange people. I lived in next door Oldbury, a superior and more civilised town, even if we didn’t have a medieval castle, a zoo designed by Berthold Lubetkin, an Alpine chair lift, a Killer Whale or pink flamingos. But neither had we been on the wrong side in the English Revolution.

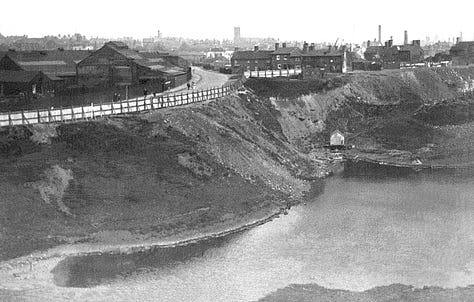

"In Oldbury we had our own kind of holes, and ours were of an entirely different magnitude. And we knew where our holes were! Dudley was careless with its holes and couldn’t remember where it left them. Ours you couldn’t miss. Most were big enough to swallow a small moon, let along half a football team. And they had a name. Marl holes.

Oldbury borders Dudley, also Smethwick, West Bromwich and Birmingham. It’s famous - at least to us - for its canals. Once upon a time, before some of them were decommissioned and filled in, we were an island, surrounded by canals. Birmingham claims to have ‘more canals than Venice’ but we had more canals than Birmingham. Fact!

Marl holes - ginormous open pits dug out during the Industrial Revolution for one reason or another - were our thing. Oldbury’s holes had been dug to get at reserves of clay - a particular kind of clay - useful for making bricks. At one time, brick making had been an important part of the local economy, presumably until all the clay and been used up. Local brick manufacturers dug holes hundreds of feet wide and deep to get at the clay, and some of the holes were on the very edge of the town.

When the supply of clay dried up, enterprising Oldbury turned instead to chemicals. We were absolute pioneers of the chemical industry. Albright and Wilson set up shop in Oldbury in the late C19th, producing phosphorus and potassium chlorate, and later expanded into silicones, detergents, food additives, metal finishing chemicals, strontium based chemicals and chromium based chemicals. It was the second largest chemical manufacturer in the United Kingdom after ICI.

Oldbury resident Edith Johnson lived in Gladstone House in the 1920s, and recalls how it was swallowed up by the marl hole where her father worked…

The marl hole stretched between the Wolverhampton Road, Portway Road, Shidas Lane and Barn Hill. It was very deep, with grass at one side and the clay at the other. My father, John Hipkiss, had worked at the marl hole since leaving the army in 1918, and was a chargehand, responsible for explosives.

My father would drill the holes and pack them with dynamite. Then he would blow his whistles to warn the workers and fire the charges to loosen the rock and clay. The clay was loaded on trolleys, and taken to the top of the marl hole. There the women would take it to make bricks, which were a blue colour after firing.

The house was threatened (by the encroaching marl hole) and we moved out shortly after 1932. Eventually, Gladstone House itself fell into the hole, leaving only the gate posts and post box to mark its place.

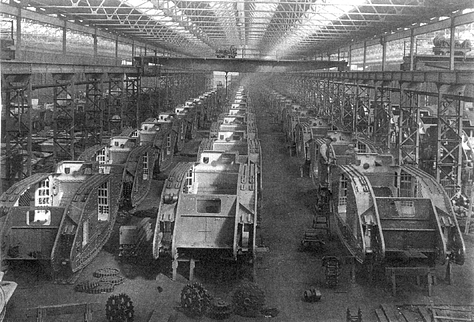

I recently learned that all of the Mustard Gas used in the First World War was made in Oldbury, as were most the tanks. It was and still is a pretty dangerous place and more than once locals have had to lock themselves indoors after chemical leaks. I also watched a documentary on the development of Britain’s first Hydrogen Bomb. I was surprised to learn that an Oldbury-born scientist - working for Albright and Wilson - had a hand in that too. Don’t thank us all at once.

So what’s the connection to holes, you might well ask? The answer of course is chemical and industrial waste. As the needs of industry changed, so Oldbury’s marl holes were transformed into chemical lakes. God knows what was in them. I once asked a local historian - my mom - and even she didn’t know, but she recalled that when she was young a boy had fallen in and never got out again.

Oldbury was a proper Chemical Town. Mr Albright and Mr Wilson, both Quakers, built and paid for pretty much everything in the town including schools, parks and social clubs. They even opened up their own bank in the town, just to pay employees. They called it Lloyds Bank. And just down the road was another Oldbury Behemoth, British Industrial Plastics, which had been a global pioneer of the plastics industry.

Back to the subject of holes. The Marl holes remained for years. Some were fenced off and flooded with something approximating water. Others, like the one opposite my Gran’s house (see photo, above) were transformed - yet again - for landfill. In the early 70s my cousins and I had hours of fun playing on the mega landfill site over the road. It was like the best adventure playground ever.

When the hole got full up of rubbish, it was flattened, turfed and converted into and football pitches and playing fields. What could possibly go wrong? What’s more, they named the whole area ‘Lion Farm’, so I am sure you are beginning to understand, I had very good reason to be paranoid about lions! That said, I did have a flat on the Lion Farm estate when I left home, and I never once saw a lion.

Currently, there’s an ongoing battle between Lion Farm residents and the local Labour council who have sold the playing fields to a developer and given them permission to build a swish retail park.

It’s a depressingly familiar story - Sandwell Council have spent the last two decades building over parks, football and playing fields and even our beautiful golf course at the top of the estate where I grew up. But with the Lion Farm fields, you have to wonder if anyone even remembers there’s a planet-sized chemical pit full of rubbish sitting underneath?

I discovered while writing this that there’s even a place called Fiery Hole, somewhere between Dudley and Wednesbury. The name apparently relates to naturally-occurring fires caused by leaking gas escapes through coal seams. These fires can smoulder for decades, causing smoke to seep up through the ground. And that’s exactly what happened around Fiery Hole.

Since I moved away, one of the Marl Holes just the other side of the Rowley Hills, filled with actual water and now forms part of a UNESCO-recognised ‘geo-park’ and nature reserve called Bumble Hole. There are even a mineshaft and geohole investigation consultants and businesses in Dudley these days. So if a giant smoking hole opens up near you, who you gonna call?

And the Moral of the Story? Resilience, perhaps? That is the resilience of nature and the landscape - you really wouldn’t know the area took such a pounding during two centuries or so of the most brutal industrialisation. And more importantly the resilience and inventiveness of the people. Growing up in a heavily polluted industrial town, where life was tough and often short, I still think it’s important to take a balanced view of industrial growth and progress.

I may have highlighted many of the negatives but for terrible things, the Industrial Revolution gave birth to the modern world and helped deliver wealth, goods and life choices way too many of us take for granted now. So maybe we could say every hole has a silver lining? And after all, Blackburn, Lancashire may have four thousand holes, but how many of them are UNESCO-recognised?